Remembering Neena Schwartz, a Pioneer and Advocate for Women in Science

Written by Kelly Mayo in celebration of Pride Month

Remembering Neena Schwartz, a Pioneer and Advocate for Women in Science

For the last newsletter issue of Pride Month, we celebrate the life, career, and advocacy of Dr. Neena Schwartz. It has been more than 3 years since the death of Neena Schwartz at age 91, and writing this brief remembrance brings back painful reminders of the many ways in which she is missed. But it also revives warm memories of Neena’s influences on her friends and colleagues, and indeed of the significant and often unrecognized impacts she had on the lives of many who may not have known her. Neena was a tremendous scientist, a leader in our broad discipline of reproductive biology, a passionate advocate for women in the sciences, and a significant role model within the LGBTQ+ scientific community.

By way of brief background, Neena was a Baltimore native and a graduate of Gaucher College who earned her PhD in Physiology from Northwestern University. Following several academic positions in the Chicago area, culminating in a tenured professor appointment at the University of Illinois-Chicago, Neena returned to Northwestern University Medical School as Chair of Biology, and later was a founding member of the Department of Neurobiology and Physiology, where she held the William Deering Professorship in Biological Sciences within the College of Arts and Sciences. Neena became interim Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences (1996-1997) prior to her retirement in 1999. Neena was also the founding Director of its Center for Reproductive Science at Northwestern, building a highly interactive and productive nexus between research and training in reproductive biology.

Neena’s research focused on the reproductive cycles of mammals. She used thoughtful combinations of physiology, endocrinology, modeling, and molecular biology to gain novel insights into the neuroendocrine control of ovarian function and the feedback mechanisms contributing to cyclicity. Perhaps her most recognized work was performed in collaboration with the late Cornelia Channing, a biochemist from the University of Maryland, and was published in PNAS in 1977. This seminal paper described a factor from ovarian follicular fluid with a primal role in the negative feedback regulation of pituitary FSH secretion, a female inhibin, and it opened up a new and critical exploration regarding the molecular underpinnings of hormonal regulation within the HPG axis.

The impact of Neena’s research, as well as her outstanding mentoring of trainees, was recognized with her election to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1992, and with the Mentor Award for Lifetime Achievement from the American Association for the Advancement of Science. There were many other awards and honors, including the prestigious Carl Hartman Research Award from the SSR in 1992.

Sometimes lost among her many research contributions was the impact Neena had as a leader, and as a trailblazer for women in science. In 1971 she was a key organizer and first co-president (1971-1973) of the Association for Women in Science (AWIS). AWIS was founded to advocate for more women in tenure track positions and on study section review panels. Indeed, in 1974 AWIS sued the NIH to stop all appointments to study section. Notably, when eventually provided with a list of 400 study section vacancies, AWIS responded by providing the names of 1,000 highly qualified women scientists. Not too long afterwards, Neena was elected as the first woman president of the SSR (1977-1978), she co-founded Women in Endocrinology, became the second woman president of the Endocrine Society (1982-1983), and was recognized by the Williams Distinguished Leadership award of the Endocrine Society in 1985.

One of my favorite examples of Neena’s activism was her response to a letter to Science written by R.G. Lynch that equated “women’s lib” to trying to “repeal nature’s laws”. Neena responded thusly: “Appealing to ‘nature’s laws’ is a time-honored and traditional way of preventing change. As a reproductive biologist, I recognize that natural laws exist. Those which are relevant to the issue at hand, namely the equality of opportunity for women, are rather small in number. They include the fact that women, not men, become pregnant; that women, not men, carry children until birth; and that if it is desired by the parents that the child suckle, it is the woman who plays this role. I do not know of any other natural law that a relevant to this issue.” (Letter to the Editor, Science Dec 1, 1972).

In her forward to her superb autobiography A Lab of My Own (Rodopi, NY, 2010) Neena described the diversity of roles and descriptions she has encountered as sometimes leaving her feeling “split at the root”, and the book being her attempt to “bring them whole” for herself. In writing her story Neena recognized that, “My third side- not the activist or the scientist- needed to come out, literally and figuratively”. While she was an inherently private person, Neena made the decision that to tell her story fully, she had to tell it honestly. In a striking passage, she discusses a “microphone fantasy”, of speaking at a conference and fighting herself not to announce to the audience that she was a lesbian. Neena writes, “I never did it- until now”. And indeed, in A Lab of My Own Neena thoughtfully and deeply explores the coming together of herself as an academic scientist, an activist for women in science, and as a lesbian. The book’s many messages cannot be captured in this brief remembrance, but I encourage you to read it!

Of the challenges she faced as a lesbian in science, Neena wrote in the book that “As a woman in science, I always felt I had the right to be where I was and that I could go as far as my abilities and desires would carry me… But as a lesbian, I could never shake off the messages that I had received throughout my teens that it was wrong, and so I was wrong. Not only did my mother not approve of who I was (my Dad and I never discussed it!), but also, neither did society. While my feminist activism has at times seemed separate from my science, it, like my career, has been played out in the open. My lesbianism, however, has always been hidden, even when others acknowledged it. It seems to me to somewhat resemble espionage living this way, where one has a “cover” (my public life) and a hidden agent identity (my private life). In that life, one’s “real” work is being a spy.

One’s cover is merely the apparent work… The downside to being lesbian with regard to my professional life, is that my support network – my partner – was never formally recognized by the external world until I was in the dean’s office at the end of my career… When things went wrong in my personal life, I could not look to my colleagues for support and this was very hard. I was reminded of this when one of the men in my department went through two serious illnesses with two family members within a few years. The rest of us were quick to help fund his lab or do some teaching for him. But years ago, when [my partner] Jan had breast cancer surgery, I kept right on working and did my grieving alone at home… Because of writing this memoir, I have now joined the National Organization of Gay and Lesbian Scientists and Technical Professionals. I decided the time had come. I attended my first meeting of this organization at the 2003 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Not many people were in the room, but it felt good to be there.”

Neena was a life-long learner, who late in her career saw the promise of molecular biological approaches to complement her physiology and endocrinology expertise and spent a sabbatical year in the laboratory of the late Jack Gorski at Wisconsin, immersing herself in applying new technology to longstanding questions, a period Neena described as one of the most enjoyable of her long career. Neena was an avid birder, loved music and poetry, and enjoyed time at her cottage in Door County, Wisconsin. Neena was preceded in death by her long-time partner, Claire Wadeson, a highly accomplished art therapist.

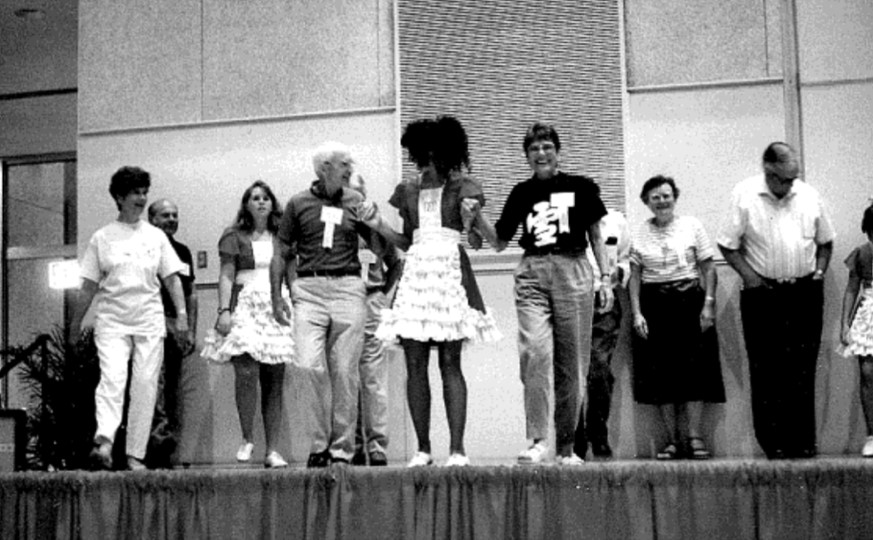

Neena leaves a strong legacy as an outstanding scientist, a fierce advocate for women in science, an inspiration to many in the LGBTQ+ community, a phenomenal mentor, and as a leader. She was perhaps one of the most critical people I have known- but at the same time one of the most supportive. This was often most evident in her mentoring and nurturing of her students and postdoctoral fellows. This close engagement with, and involvement of, trainees is of course a hallmark of the SSR, and Neena often cited this as a key element of her fondness for the society, writing in her memoir that “I have loved the openness and non-elitism of this society. I was its first female president in 1974, and I have been followed as president by many other women. Not surprisingly, the society has also welcomed trainees, giving them travel awards and prizes for excellent papers and places on the governing board. Before I retired and closed my lab, the annual SSR meeting was always the favorite yearly science event for me and my trainees.” Indeed, the very first picture in A Lab of My Own shows “Dance evening at the SSR- 1992”- check it out!

Photo Captions:

1st Image: Dr. Schwartz at the microscope

2nd Image: Neena Schwartz and her long-time partner Claire Wadeson

3rd Image: Dance Evening at the SSR. From L to R: Janice Bahr, Harold Spies, Phil Dzuik, Anita Payne, Neena Schwartz, Gordon Niswender

-Kelly Mayo

Walter and Jennie Bayne Professor of Molecular Biosciences

Dean of the Graduate School and Associate Provost for Graduate Education

Northwestern University